[dc]T[/dc]oday I want to continue from last week’s post on Fibonacci ratios, and wrap up with a few thoughts and conclusions. That post was very heavy on data and charts, but the conclusion is pretty simple: at least in this sample of market data, using this particularly specification for swings, we find no evidence that Fibonacci ratios are significant in the market. A few questions flow logically from this statement: why so many qualifications (in this sample…)? Why are Fibonacci ratios so commonly used in technical analysis? What could we have missed with these tests?

Taking these in order, the reason there so many qualifications to my statement is that any test of market data is only valid for that particular sample. Of course, we spend a lot of time and energy thinking about how to create that sample so that the results will generalize to other market data. That’s the whole point of any analysis, but maybe we are wrong in assuming the results will generalize. In this case, I took a very large sample of markets from different asset classes over a fairly long time period that encompassed many “types” (regimes) of markets. I think this is a representative sample of all market action, but, again, maybe I’m wrong. I looked at daily data. Perhaps I needed to do weekly or monthly or hourly or some other interval. (For what it’s worth, I have reproduced much of this work on other timeframes and other time periods and found that the results were substantially the same.) Also, any test we do is a joint test of both the underlying market tendency we are trying to capture and our particular specification of that tendency. This is important to remember. Maybe I should have defined the swings differently; there are probably a few hundred other ideas and ways we could think of to do this. I did quite a few of those (again, not presenting the results here), but we can never say we have definitive proof or disproof if we are thinking in a scientifically correct way. However, the statement we can make, that we find no evidence of Fibonacci ratios being structurally significant in the market after a large battery of tests, is elegant and, to casual ears, maybe understated, but, for an objective analyst, it is as subtle as a cannon shot. It is condemnation of the idea of using these ratios in trading, so we need to ask why they are so commonly used.

Here, I’m speculating. I don’t really know, but I think there a few answers. Much of technical analysis borders on superstition, and people accept old ideas as somehow descending from authority. People like mystery and intrigue, and I think the idea that your trading system somehow rests on the harmonic convergence of the Sacred Geometry of the Pillars of the Universe (that phrase probably needed some more capital letters) appeals to a certain mindset—people will overlook the aberrations of the Gann/Elliot/Fibonacci crowd. Books like the DaVinci Code appeal on a deep level, and trading systems based on mystical concepts are hard to test and also immediately appealing. Vague claims abound since most of the gurus of these methodologies are long dead; Alexander Elder recounts an interview with W.D. Gann’s son in which he disclosed his father’s complete inability to make profits trading, but many websites and books still list Gann as the “most profitable trader ever. Ever.” Let’s face it, these ideas are sexy, and it is very easy to sell a newsletter trumpeting these concepts, even if they have no objective utility. There is also something reassuring about being able to forecast exact turning points to the tick, even if there is no validity to those forecasts. If you make enough predictions, some of them will work out just by chance, and that’s all you need to embed a pretty deep cognitive bias. Profitable trading may seem just out grasp, but you “know” the method is good because you can remember some great forecasts. Something must be wrong with your psychology or money management, so attention is focused there while the real problem—the fact that the underlying methodology may not have an edge—goes largely unexamined.

Here, I’m speculating. I don’t really know, but I think there a few answers. Much of technical analysis borders on superstition, and people accept old ideas as somehow descending from authority. People like mystery and intrigue, and I think the idea that your trading system somehow rests on the harmonic convergence of the Sacred Geometry of the Pillars of the Universe (that phrase probably needed some more capital letters) appeals to a certain mindset—people will overlook the aberrations of the Gann/Elliot/Fibonacci crowd. Books like the DaVinci Code appeal on a deep level, and trading systems based on mystical concepts are hard to test and also immediately appealing. Vague claims abound since most of the gurus of these methodologies are long dead; Alexander Elder recounts an interview with W.D. Gann’s son in which he disclosed his father’s complete inability to make profits trading, but many websites and books still list Gann as the “most profitable trader ever. Ever.” Let’s face it, these ideas are sexy, and it is very easy to sell a newsletter trumpeting these concepts, even if they have no objective utility. There is also something reassuring about being able to forecast exact turning points to the tick, even if there is no validity to those forecasts. If you make enough predictions, some of them will work out just by chance, and that’s all you need to embed a pretty deep cognitive bias. Profitable trading may seem just out grasp, but you “know” the method is good because you can remember some great forecasts. Something must be wrong with your psychology or money management, so attention is focused there while the real problem—the fact that the underlying methodology may not have an edge—goes largely unexamined.

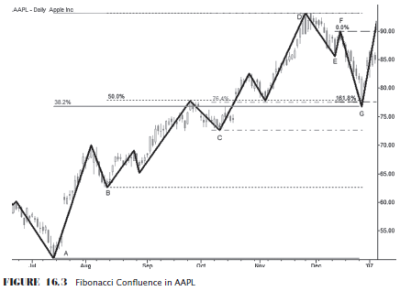

There is also another influence, and this is that people are unable to subjectively evaluate the significant of any level or line in the marketplace. (Watch this video, and track those levels over the past years for an interesting insight.) This is not meant to be insulting to anyone—it’s simply a function of the way our brains see patterns in random data. Any line drawn on any chart at any time will most likely be significant. Put several retracement ratios and confluences from different swings and different timeframes on a chart, and you have a “can’t miss” system. Your eye is virtually guaranteed to find significance. This is perhaps why so many people defend these levels, but the real question is, say, for instance, you enter trades at the 38% retracement and place your stop beyond the 62% retracement, does that work? Does that work better than putting your stop or entry someplace else? I’ve never seen a well constructed test that suggests that it does for any trading system.

Some people will suggest that Fibonacci analysis is an art and that it’s wrong to subject it to actual analysis. They’re at least half right: I think that market analysis always includes a significant element of art, but we still should quantify everything we can. It’s hard to accept that these ratios are both extremely important and invisible to quantitative tests. If we can’t tease them out of the data with statistical analysis, maybe they aren’t there? I think the real answer to the art challenge is that we don’t need these ratios to do excellent analysis. There’s no proof they add anything to our thinking.

That is perhaps the most significant point, at least to my thinking. Occam’s razor applies here: the simplest theory with the greatest explanatory power is probably the best answer. I live in world in which I believe that market prices are driven by the simple interaction of the desires of human participants to buy and sell assets, whether through direct action or proxy. (A computer program encoding elements of market behavior into an algorithm is a proxy. It is still a concept driven by human cognition and analysis, and a human can always make a decision to stop the algorithm from trading if market conditions change.) That’s a pretty simple construct—everything you see in the market is a result of the interaction of those convictions, the underlying behavioral patterns and cognitive quirks of humanity, expressed, in the end, in market prices. I do not need a code that is derived from counting the letters in the King James translation of the Bible. I do not need mysterious ratios or arcane wave theories to explain, and to predict within the statistical bounds of what probability, the future path of price and/or volatility.

So, that is why I personally do not use any retracement or extension ratios in my analysis or trading. It wasn’t always like this; I still have some very cool spreadsheets for calculating ratios and confluences, created in my salad days (“when I was green in judgment…”) before I learned to apply basic statistical reasoning to market action. If you do use these ratios, I would challenge you to think deeply. Perhaps I have missed something significant, or perhaps I am merely completely wrong in my analysis, but one thing should be clear—the burden of proof should lie on the people offering arcane and complex methodologies, when simpler methods work just as well or better in the marketplace. If Fibonacci ratios are the key to the markets, where are the quantitative tests? Where’s the proof?

Adam, regarding support and resistance levels: Are you not using them? I thought you take swing highs and lows for entry techniques and also for putting stops around it.

In some cases, yes, but I use S&R far less than most people. I already talked about this in the first two weeks of the course and we will cover it again in the coming weeks in more detail, but, basically, only use crystal clear levels that are obvious to everyone. Clear, visible chart levels. There are no hidden levels!

that video was interesting…it makes perfect sense! support and resistance is everywhere because the way our eyes search for it…good stuff…but it brings up a question…if everyone uses S&R then doesn’t that make them significant?

Logical, but then you’d see significance in the data, and that doesn’t happen. So many of the tools of technical analysis show no more statistical edge than a coin flip. Why not use the ones that do?

Why are Fibonacci ratios used in technical analysis? Maybe because you see yourself clueless in front of price action and you have to use something, anything, you have to justify your gambling using some ‘proofs’. You don’t want to test if Fib are supported by some statistical evidence because you are either inapt, lazy or afraid of the result (what will you use in the future if you demonstrate yourself Fib are useless?).

There’s some truth to what you’re saying here, I think. People need to be shown that there is a better way and that you don’t have to rely on untested tools. Think critically and question everything.

Dear Adam,

My take is that it is practically impossible to test whether Fib levels work or not using a computer. IF you are simply taking Fib levels as retracements and testing them it will not give you desired results. If we use Fib levels in isolation then they will give you poor results. Use Fib levels with two degrees of trend and combine them with structure the results will be better. I do not use Fibs in isolation. It is just another tool.

Regards,

Manish

Well, Manish, respectfully, I think you might have missed one of the major points I was trying to make… perhaps I didn’t say it clearly enough… but I think the idea I was trying to get across was if Fib levels are real, shouldn’t retracements tend to stop there more than at other levels? If you use them in combination with other tools, are you sure they add value? Could you do as well without Fibs? How do you know the answers to those questions?

These are the kinds of questions I want to encourage people to ask–work toward an objective, scientific approach to trading.

I’m not saying I’m right, but the “you can’t test it” mindset seems like an easy out… I just showed you a way we should be able to test it… maybe there’s a better way. Maybe I made a mistake. Maybe I missed something. (All of those are possible.) But don’t default to “you can’t test it” without really being able to explain why.

First of all, thank you for taking the time to do real scientific work here.

I just wanted to add that testing confluence of fibs with something else would be a separate test that still could show profitability. You might very well end up with reduced sample size problems doing this, as you will find confluence can be quite rare, so you might have to get several years of market data (of course that depends upon how stringent you make the test).

So you have already tested fibs.

Then you could test say pivot points (hint, they are weak at best).

Then if you combined the two to create new confluence levels, you test that for profitability.

I am more interested in the answer because I believe like you said that people see patterns just as we did in the stars or the moon. But I could be wrong, maybe when you do combine fibs with something else you get statistically profitable trade given and R/R ration.

You do have a point, but it increases the complexity of the project considerably, and introduces more opportunities for data mining-type errors. There may well be another way to test this stuff, but I’ve always tried to err on the side of clarity. The confluence issue is certainly something I’ve thought about, but I do think enough people make enough claims for Fibs that we should expect to see them in the raw data with some significance too… the fact we don’t (and that my trading works quite well without them) was enough to kill any interest I had in digging deeper.

For ease of discussion I will talk from a buy standpoint near support.

The question of self-fulfilling prophecy of technical analysis (i.e., if enough people believe in fibs then they are are true) has always intrigued me. On one hand if there are enough people buying at Fib support X, then it will go up from that support, on the other hand once all the “fibers” are in, if there is no more reason to buy then thats it, additionally the more people who are JUST trading the fib at that level the more likely they are to all fall down together and the worse price the latecomers are getting filled in at.

At the end of the day the movement of the market up comes down to buyers overtaking the market sell orders. In order for that to happen buyers have to be convinced to buy there, which means a whole lot of reasons both fundamentally from larger institutions, and technical from retail.

Even as a successful trader it still to me is a very interesting puzzle for not just fibs, but to consider a market equation much like an equation for the universe. Something that I feel is harder to obtain the closer you get to it. An equation that will for the most part predict price.

Pingback: Should We Stop Using Fibonacci Retracements? |