[dc]I[/dc]n a post last week, I talked a little bit about the kind of commitment and emotional charge that I believe it takes to truly excel in any field. Whether you are doing a martial art, studying music, learning to cook with excellence, or learning to trade, it’s going to be a long, hard road. Passion and desire, while essential, are not enough–you also need to have some strong learning strategies and be prepared to overcome the challenges you will face. Today, I wanted to write a follow-up post focusing on some of the things that I learned about skill development as a top-level classical musician. I think all of these apply in one way or another to trading, but I am going to leave it to you to connect the dots. I hope that at least a few of these are good food for thought:

- One of the keys to developing skills is consistency. It is not possible to develop a high level skill without repeated, consistent exposure… rehearsal, practice, or whatever you want to call it.

- Long practice sessions are not incredibly important, as what is done at the beginning and end of the session is most valuable for longer-term retention. If you have 3 hours to work, it may make sense to break that up into 20 minute sessions with 2-4 minute breaks in between. Of course, this tests your conviction because many people will go on one of those short breaks, punch up a video game, and never come back.

- It is well known that your brain continues to work and process while you are not actually involved in the practice activity, if (and this is key) you have constant, repeated exposure. Progress actually seems to be made more in the “off times” than while you are actually working, but it is the hard work that causes the advance in skills. I can remember struggling for hours as a developing musician with a difficult passage to no avail, feeling that I had made no progress in the session, moving on to something else, taking a break, and coming back to find that I could play it flawlessly. It wasn’t magic—it was due to many hours of concentrated work finally coming together when I moved my focus somewhere else..

- Sleep is important. This is an extension of the previous point, but a lot of progress is made while we sleep. If you are dreaming about the activity, your brain is probably still practicing and developing the skill—this may well be part of the process by which those physical changes happen in the brain. If you aren’t dreaming about the activity, then you probably aren’t working hard enough. (No joke.) In addition, work done immediately before sleep seems to almost be “supercharged”. If you can study something or work on something and immediately fall asleep, the overnight progress is usually very impressive.

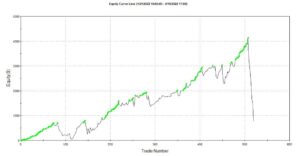

- Over the longer-term (months to years), progress is not linear, but is more of a step function. Again, musicians know this only too well—you will work for weeks and weeks, and sometimes even have the experience that you are actually getting worse at what you’re doing. (Let me tell you, that is awesome, especially if you’re putting in solid 6-8 hour days.) Then, in a sudden burst, you will wake up one morning and have made amazing progress seemingly overnight. What has happened is that the hard work finally paid dividends, but it can come after many weeks or months of seeing no progress. Your growth will not be a line or curve… more like a series of plateaus and steps. Most people get lost here because they lose faith on the plateaus.

- Great learners are captivated by the process of getting better. The goal may be motivating, but the struggle and work itself is rewarding in its own right.

- Most people experience that as they move closer to mastery, they are more fascinated by a focus on simple fundamentals. As a musician, this might mean focus on simple building blocks of technique long-ago mastered, or on simple pieces that are well below the artist’s ability level. As a trader, maybe it means losing the indicators, charting by hand, and focusing on simple fundamentals of trading. Beginners tend to be entranced by flash and glamour. Experts often bring a profound focus to simple fundamentals of their art.

- Emotional state really matters. (See this Newsweek article that mirrors many of these points.) Perhaps this is why that “rage to master” is so important–being emotionally involved in the process actually makes you learn faster. Good coaches can help, as can being in the right environment, but, in the end, I think a lot of this must come from the individual. If you can make it fun, make it play, skills will come faster.

- Visualization is a powerful tool. Musicians have been doing this for a long time. (One of my teachers learned both books of Bach’s Well Tempered Clavier as a child without ever touching the keyboard, performing the entire 5+ hours of music from memory the first time he sat down to play them. This type of seemingly super human feat is not that uncommon, actually.) Visualization is most powerful when it augments and extends work being done physically as well, and, in my experience, may be more useful for a master to hone and develop skills than for a beginner to build those skills.

- High level skills are assimilated beyond the level of conscious thought. For instance, playing a rapid passagework often involves such accurate timing that the critical ear can perceive imperfections of just a few milliseconds. This is far beyond the conscious mind’s ability to manage—there is no way, for instance, that the brain can micromanage the muscular coordination required to produce a perfect scale in a Mozart concerto. However, years of practice build a technical ability that allows many of the details to be managed by the performer’s subconscious–eventually you own that skill and it is part of you. It we do it right, it looks very easy… so easy that you lose sight of the complexity and it looks like anyone could do it. (Anyone probably could do it, if he is willing to give up ten years or so of his life to do so!)

- Chunking, learning to see in units and chunks rather than individual units,is an important component of mastery. Just as good readers do not read the sounds of each letter, but see words and whole phrases as units, good musicians don’t see notes—they see phrases and passages. Masters in all fields use this skill. A competent chessplayer can glance at 4 games in progress and easily reproduce, from memory, the board positions for each one, but if you give him one board with randomly arranged pieces, he probably will not be able to do it. How? Because he doesn’t see individual pieces, he sees them as meaningful units that arise in the course of a game. He doesn’t see, say, 14 individual pieces in a middle game, he sees 3 or 4 “chunks” that he recognizes. If the pieces are randomly arranged, he has no edge and can’t do any better than you or me.

So there you have it… maybe some food for thought as you work on refining your trading process and consider your next steps along the path to mastery.

Great insight to Hone any Skill ! Thank You !

Pingback: Saturday links: unfortunate realities | Abnormal Returns

Pingback: Evening Bamboo InsightL 14 Aug 2014 | Bamboo Innovator

Great stuff. Thanks Adam.