Trading a Powerful Trend in Gold

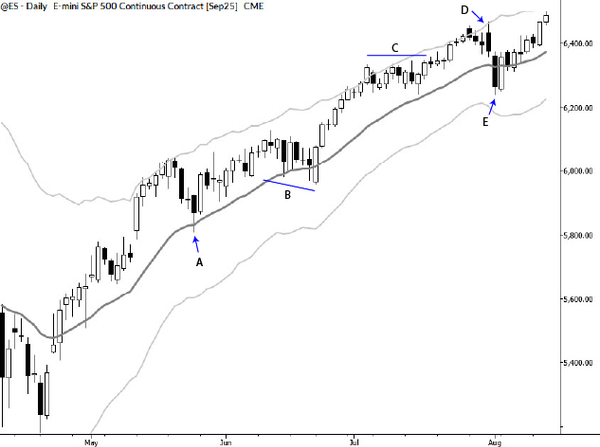

There are many ways to trade financial markets. Much of the struggle and confusion that traders face comes from not understanding their goals--not knowing how they want to trade. In some very real sense, from not knowing themselves. Gold (and precious metals in general) provides some good examples for traders