When is a human better than a machine? Using human discretion in quantitative testing.

First, thank you to each of you who participated in the experiment/quiz. We have stopped collecting data, but you can re-take the quiz and see which answers were right or wrong here.

Let me start with the conclusions up front, and then I’ll explain what we did and why.

- We looked at two types of levels. In intraday S&P 500 futures, we looked at action against the previous day’s high and low and against the overnight session high and low. In the EURUSD, we looked at action around “round numbers”.

- We used a methodology designed to see if humans could tell if a level was “real” or “fake” by presenting the levels against actual market data and against market data which was price-shifted.

- The baseline assumption of the experiment was that no level was valid. If humans picked the correct level or showed a strong preference for one level, this would be information that would contradict that baseline assumption. (This seems convoluted, but it’s actually proper experiment design. More on that later.)

- We saw that humans were able to distinguish the levels in the S&P 500, suggesting that there is validity (and, potentially, utility) in those levels. We did not see these results in the EURUSD. This strongly suggests that our S&P 500 levels are valid, and that the EURUSD does not show any unusual activity around round numbers.

There’s a lot to unpack here, but I’ll try to keep this post reasonably short.

The questions

When I was an active daytrader, I focused heavily on three sets of levels: the previous day’s high/low, today’s high/low, and the Globex (overnight) high/low. I had countless trades, stops, and targets motivated by those levels. My strong belief, at the time, was that they were important levels, but, as I’ve tested more and more things over the years, I discovered that many of the tools I once thought important failed in testing—maybe these would also fail?

I’ve recently been doing a literature review of the best books on price action trading, and Bob Volman, who is widely accepted as the expert on forex price action, lists the “round number” effect as one of the seven most important principles of price action. Bob suggests plotting the round numbers (you can find details of what these are in his books) as grids on charts, since they are so important.

To me, this is a potential "uh oh" because I know that cognitive bias makes any line, even a gridline, appear to be significant. My eye didn’t see anything significant around round numbers beyond what I thought I could chalk up to cognitive bias, either in the myriad examples in his book or in live markets, but maybe I’m missing something?

Those were the two specific levels I set out to investigate, but I also wanted to explore using the human power of pattern recognition in a structured test.

Testing levels

Testing levels is not easy. I’ve worked with various statistical frameworks over the years, and none of them are fully satisfactory. The problem is that any test is a joint test of whatever tendency might (or might not) exist in the data, and the specific test structure you create. If we test with statistical tools, we have to define those test structures precisely, and they all have blind spots.

But if we back up for a bit and ask what we expect of a “level” in the market, I think it boils down to this: we expect something to happen there more often than could be explained by chance. (Indeed, something can happen at any random price level!)

Here’s a list of “somethings” and you can probably add more:

- Price might stop at the level

- Price might be drawn toward the level

- Price might oscillate around the level

- If price goes through the level, it might act in reverse on a retest. (The so-called principle of polarity from technical analysis.)

- Price bars might close more often near the level

- Price might accelerate through the level

There are many more possibilities, but we can see, even from this short list, that some of those things are almost exactly opposite. It’s entirely possible they could balance each other out in stats, so a simple quant test might see no effect.

But it’s also possible that an experienced trader’s eye might be able to make use of the information and sort out those different cases.

So, I thought about a way to incorporate that human discretion into a test.

Discretionary test structure

Remember, our assumption is that a valid level would do “something” to price. Though it’s not a perfect analogy, imagine you are looking top down at an animated map of cars and trucks on roads. Now, make that map nighttime, so that all you can see are the bright points of cars and trucks following roads. Take a moment and picture this in your head.

This is not a perfect comparison to market data because the cars are restrained to clearly defined roads. Market data is much messier, but the test idea is easiest to understand from the map.

Imagine now I overlay a set of randomly drawn roads on that map. (Call this “fake roads”.) And then I take the same set of randomly drawn roads—remember, these are not the actual roads cars are following—and I shift it 1 km north. (Call this “fake shifted.”)

Now, what if I showed you both “fake roads” and “fake shifted” on the map and asked you which roads the cars followed more closely? You would probably shrug, decide they both look bad, and just pick one. If I play this game with 1,000 people, don’t you expect that about half of them would choose either fake? Since they are basically random lines, one set is probably not going to look a whole lot better than the other.

Ok, stick with me: Now, I show you another set of roads. One is the actual roads (“real roads”) overlaid on the actual map. The other is the actual roads, shifted north 1 km (“real shifted”).

If I show you these and asked the same question—which roads do the cars follow more closely?—it’s very likely you will pick real roads. If I show 1,000 people this test, we should have almost no votes for “real shifted”.

So this is the essence of the test: I proposed that if a level were valid and real—meaning that it had some influence on prices—humans should be able to tell the difference.

So, I created a test:

S&P 500 test

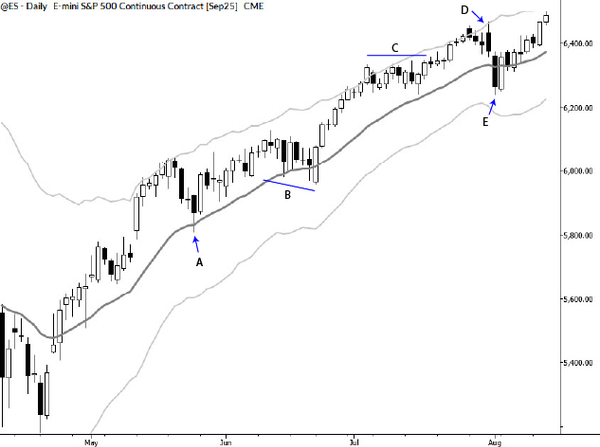

I plotted yesterday’s high/low and the overnight high/low on 5 min ES futures bars. Each chart showed only the current day, so it was not possible to anchor the lines on the screen to previous price points. The trader had to simply accept them as-is. These were the “real SP levels.”

I then shifted the price bars randomly plus or minus 20% of the daily ATR. (I could have accomplished the same thing by shifting the levels.) If the levels were valid, this was enough of a shift to obliterate them. I hid all labels on the X and Y axis of the chart, leaving only the price bars and the levels.

EURUSD test

I plotted “round number” grids per Bob Volman’s instruction on 5 min EURUSD bars. I used the time periods he studied in his book, to remove any concerns about the market somehow changing. This was a time period in which a price action expert had deemed these levels to be highly significant.

Round numbers, used in his book and work, are, e.g., 1.3300, 1.3250, 1.3200, …

I then shifted the price data “half a round number” (.0025) which should have obliterated any round number influence. (Though this does open us up to the argument that perhaps “half round numbers” are significant, where does this argument end? It is not possible for every price level to be significant.) Again, I hid all axes labels.

Overall test

Tom and I created a quiz format that asked for trader input on 10 EURUSD and 10 S&P 500 charts. I randomized everything, including the choice of days. We all know that levels work better on some days than others, but I wanted to remove any influence on my part of the test creation. I set the timeframe to several months, but the specific days, order of questions, and order of real/shifted were randomized for each question.

Tomorrow, I will write another post sharing the detailed results, and what I think this means.