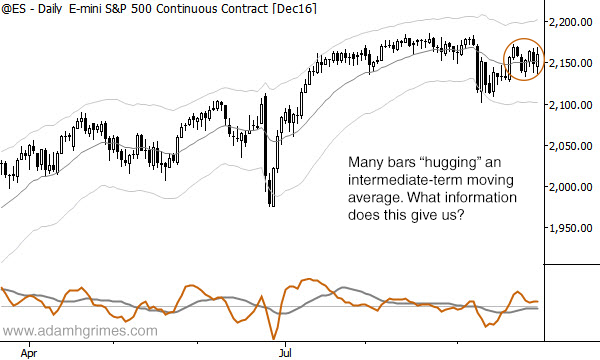

One of the keys to discretionary trading success is knowing when not to trade. Here’s a simple chart pattern that can help filter out some of the good times from the bad, and it works on pretty much any market or any timeframe. Take a look at the recent action in the S&P 500 index (daily chart, 24 hour session):

Here’s the simple rule: when a market spends a lot of time around an intermediate term moving average, the market is probably in relative equilibrium. Since every edge we have, as technical traders, comes from an imbalance of buying and selling conviction, those are markets in which we do not want to participate. Those are markets that are likely to be more random, and random price movement is what slowly grinds our trading accounts, and our mental fortitude, to dust.

Now that’s the broad concept, but I’d recommend you refine it a bit and make some firm rules before you use it. Consider the first sentence of the previous paragraph; you need to define at least the following concepts: 1) what’s “a lot of time”? How many bars does the market need to spend around the moving average? 2) What does “around” mean? In the example above, it was clear because the market chopped back and forth through the average, but is there a more precise definition you could use? 3) What kind of average and what period will you use? 4) How do you boil this down into trading rules? 5) Might those rules be different if you were thinking of entering a position or already in a position?

In general, I think most of the things people do with moving averages do not make sense. Moving averages do not provide support and resistance; that’s an illusion you are seeing on the chart and it isn’t real. There are no special moving averages; the 200 day is no more important than, say, the 190 day. (Read more here.) Moving averages, crossing of various moving averages, slopes of moving averages–none of these work as reliable trend indicators. But here’s something that does work. What we are looking for is not a specific signal from a magic number, but a broad concept: when a market is moving relatively sideways, there’s quite likely no edge. We can avoid being in that environment and wait for better trades–a good use of both mental and emotional capital. This is a way to use a technical tool to illustrate the broad concept, the underlying mood of the market, and then you can craft trading behavior to match the mood of the market.

This isn’t a profound trading rule, but it is another one of those little things that can make a big difference. When you have a lot of those little things aligning in your trading, you have the difference between success and failure.

Now I am baffled…

The concept itself was probably one of the first I learned from you and likely of the most simple and useful. But honestly, I would have expected an issue like this to be part of the discretionary tool set.

There are for sure many ways to quantify the concept, but I struggle to develop a quantitative rule for my discretionary approach here that is still simple (or not overfitted).

E.g. the set-up to the 9/12 drop looks attractive although the price was chopping forth and back the EMA20 for quite a few days. Or take the chart, modify the data and make the drop on 9/12 maybe 20 points deeper. Prices would still crisscross EMA20 the last few days, but the set-up would seem attractive as a first pullback in a potentially emerging downtrend.

I might have to look into my tea leaves later today… 😀

Perfect timing and great article. I needed this today(just got butchered). I guess I sort of knew this but you worded it from a voice of experience, which is what I am lacking.

Pingback: My Favorite Trading Articles: Week 10/15/16 - New Trader U -

Not quite sure. I don’t think you would know a consolidation before it really happens. Say if you define 10 bars around a MA as the market consolidation period, you are taking the risk that the market is already at the end of its consolidation and ready for the next massive directional move. I would rather use a price range to define consolidation. Market moves between narrow price ranges. The movement within a particular range is quite random. However, when a market moves out of a range and hasn’t formed the next range, the movement is directional and somewhat “predictable”. The difficulty to catch these directional moves is the fake breakout.

Hi Adam,

I have been listening to your podcasts and reading your blog for a while. I like your straightforward approach and have been throught the “pain” of having a ridiculous number of Technical Indicators on a chart. Now I just use a chart to back up my “intuition”- if I am correct, you did a Podcast on that topic so it came from you.

Being an options trader, there are a few items that are more important than any chart (in my opinion). If the ETF or stock doesn’t have volume, liquidity, etc. then I won’t go through that pain again either! I am still reeling from some of the losers I had.

Having said all of this, what do you think about an Iron Condor Strategy on something as heavily traded as the SPY or a good Blue Chip that pays a good premium (volatitly rules then).

Since we are coming up on a major event, not long term, perhaps 30 days or so, but noboday says it needs to be held to expiration right?

Thanks – your feedback (perhaps confirmation), that I FINALLY am learning at bit, although it will never stop, will be appreciated. On the other hand, I can handle blunt criticism too. Too many hours and $$ spent so there is no ego here.

Saludos,

Val