Over the years, I’ve had my fair share of being on both the right and wrong side of world events. However, on balance, I’ve noticed an unusual number of times that I am in trades that appear to have somehow predicted the future–whether being in a commodity, a currency, or a regional stock market in advance of a crop report, policy announcement, or some other significant development. Now, I don’t think anyone can predict the future, and, as I’ve written many times before, the predictive power of any methodology is only valid within the bounds of probability and statistics. In other words, I’m never going to be one of the guys you see on television pounding a desk saying that such and such “must happen” or “will happen”; all I can say is that probabilities favor one resolution over another, and good odds, realistically, might be 55%. Understanding this certainly helps to keep us humble and to moderate our confidence.

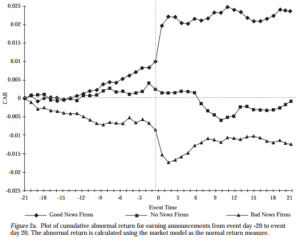

But we are still left with the question of why, so many times, positions and trades do appear to be put on in advance of significant economic developments. I was re-reading some academic research this weekend, and read the classic MacKinlay 1997 Event Studies in Economics and Finance (available here), which is a good paper for anyone who wants to do serious market research to read. This paper includes the following graph:

There are three lines on this graph, for three groups of stocks: stocks with positive news, stocks with negative news, and stocks with no news. I added a dotted line for zero, and also a vertical dotted line for the “zero date”. Somewhat predictably, this graph shows that stocks that had positive news went up after the news release, and continued to drift higher. Following negative news, there was a downward spike and a recovery. Consider that both lines are composites of many stocks and many events, so there is, of course, a good deal of noise and many potential complications. ((Note, also, that the “no news” line does show some interesting artifacts. Just a word of warning: it’s easy to be misled by first level analysis. If we saw that output from a simple system test, we might think we had something that led to stocks selling off after a few days and then recovering, but this is just noise in the data. Spend some time playing with data and analytical techniques to develop a sense of what we can see even in randomness.))

What I find really interesting here, however, is what happens before the “zero date”. Think about what these lines represent: composite returns for stocks that had news. Why, then, does the line for “good news” stocks go up before the event date, and why does the “bad news” group tend to sell off before the event date? Theoretically, this should not be possible unless the news is somehow known to some group of people. (If you think markets are a fair game, you’re in the wrong business.)

Though this is far from validation of technical tools, there is an important lesson here: information leaks. Information leaks, and it has an impact on price. It is not too difficult, then, to imagine that, if we could analyze price patterns in certain ways, we might be able to tease out the impact of this information before the event is well known to the public. We cannot assume that this is easy, or that it can be done always, with any degree of reliability, but it is at least conceivable that it is possible to do so.

Though markets are complicated and competitive, and whatever edges we can find are small and often fleeting, here is concrete evidence that prices do sometimes move in advance of events. Maybe there is a point, after all, to our efforts to understand the patterns in prices, to tease out reliable edges from the morass of noise and confusion, and perhaps here is justification for why price-based approaches to trading might find an enduring edge, and for why, sometimes, we might appear to be able to predict at least some small bit of the future.

Pingback: Monday links: staying the course | Abnormal Returns

In my view, the graphs do hardly show any predictive value but rather for the most part a continuation of trend plus the fact that volatility increases with news events. For example, if we just fit a straight line for all points from -20 to -1, the news event leads to the price spiking away (in the direction of trend) but at day 20, the price on average will have behaved according to the straight line.

If that were right, that IS predictive value, though, isn’t it? 🙂

After a second thought, I think you are right. 🙂

Hi Adam. Just wondering if you’ve actually attempted to put this information into trading. Perhaps with options? I was just playing around with earnings announcements today, to see if there was any predictive value beforehand.

No, and I wouldn’t assume there’s a direct connection to trading. Just because the information is there doesn’t necessarily mean it can be exploited in an economically significant way, but maybe it can! It’s something I haven’t really looked at much, but there might be something there.

Thanks! It’d be a tough phenomenon to backtest, that’s for sure.