I initiated a short in crude oil back in July, and an astute reader sent me a good question. For many weeks/months I had been operating with the assumption that crude oil was probably putting in a long-term bottom based on the action back in March/April of 2015; his question was how and why did I take a short against that bias? It’s a good and instructive question, so I thought I’d share the answer with you here.

One of the advantages of writing about financial markets and publishing that work every day is that I have a record of what I was thinking and saying at any point in time. As I’ve written many times, I think journaling is one of the key skills of professional trading–this is a form of that. Let me set the background with some charts from a few months back.

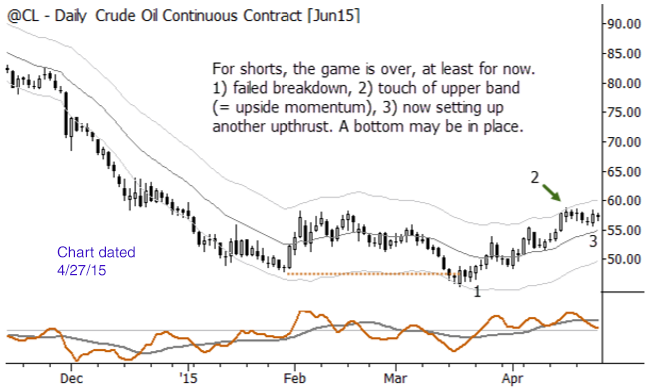

A good place to start is in the aftermath of the 2014-2015 selloff in crude oil. The market bounced in Feb 2015, set up another short attempt that more or less ran out of steam around the previous lows, and then rallied strongly off those March lows. In early April, I began to work with the idea that crude may have just put in a bottom. A chart says it better:

Over the next few months, this thesis appeared to be playing out, but it’s important to remember that a bottom is a process. We don’t (usually) identify the absolute extreme of a move and then expect the market never to return. No, it’s far more likely that the market will go flat a while (check), and perhaps even re-test the previous extreme. This is normal, and it may even be those retests that really hammer the bottom in place. It’s easy to imagine hoards of traders thinking that crude oil is going to $20, entering short on a breakdown, and then watching in dismay as the market explodes to new highs after barely taking out the previous lows.

A market will do whatever it can, at any time, to hurt the largest number of traders.

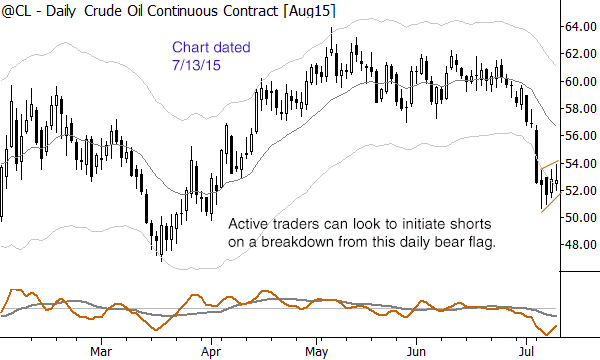

This, in fact, is nearly a principle of market behavior: a market will do whatever it can, at any time, to hurt the largest number of traders. That’s not just cynicism, I think it’s a legitimate consequence of the true nature of the market. Now, we certainly don’t want to be one of those gullible traders who gets tricked into shorting at exactly the wrong time, do we? So what do we do when the market gives us a nice, fat pitch right over the center of the plate, like this?

And just to complete (or, perhaps, to further complicate) the picture, here’s the weekly chart from the same day:

So, just to clarify the situation, here, in some bullet points, are the most important elements of market structure at the time we might have been thinking about a short entry:

- Within the past year, this market had a historic decline. Many people are inclined to think too far, too fast, and that the move will reverse. On the other hand, maybe something fundamentally has changed. At the very least, we need to be aware that these might not be “normal” market conditions.

- After that historic decline, oil put in what looked like the first part of a bottom: a retest of lows, strong upside momentum off those lows, and then daily consolidation patterns breaking to the upside.

- Following that step, the market went flat and dull, perhaps setting up a breakout trade.

- That breakout was to the downside, and a clear daily bear flag formed after the breakdown. Taking a short could mean going against the longer-term bottom (if it is forming), so what do we do?

Many traders end up paralyzed with multiple timeframes as it’s easy to get overwhelmed with information. This is obviously a mistake, but there are also gurus who oversimplify the subject, saying, for instance, to only take a trade when it lines up with the higher timeframe trend; though this idea is elegant and appealing, it falls short on several counts. For one, the best trades often come at turns, and if you wait to see an established trend you’ll miss those trades, and, even more importantly, the moving average-based trend indicators people use do not work like they think. (In fact, when a moving average trend indicator tells you a market is in an uptrend, at least for stocks, the stock is more likely go down!)

Managing the conflicts

How do we resolve all of this? I think this is a question that every trader must answer as part of his or her own trading plan. The one thing you probably cannot do is take each case as a new thing and try to make up rules for each situation. It’s far better to have a plan and to then to follow that plan with discipline. For me, the answer is that a trade is just a trade. I have never been able to prove that having multiple timeframes aligned actually increases the probability of those trades. (Though, those examples do sell books!)

The way I think about it, if I have a higher timeframe trade that points up and a lower timeframe trade that points down, one of those trades will likely fail. I don’t know which, and I can’t know which in advance. If I knew the higher timeframe trend was more likely to work, I’d just trade that one, but, in all intellectual honesty, I don’t know that. No one does. It’s possible that higher timeframe trend will fail because of the meltdown on the lower timeframe, and if I’m positioned with that lower timeframe then I will be happy. It’s also possible I will get my first profit target even if the higher timeframe pattern “wins”, so I may be able to make money on both sides of the trade. Perhaps I want to skip the lower timeframe trade and just look for a higher timeframe trade around the previous low–that’s also a viable strategy.

What matters is that I know what I will do in advance, and that I am honest about the limitations and constraints. We can only work within the laws of probability, and there are certainly limits to what can be known. It’s not a question of my competence as a trader, but of molding the methodology to fit the realities of the market. A trade is just a trade–avoid complications and simplify.

This is helpful and interesting analysis. However, I’m a little conflicted. In your book you discourage trading when an instrument is in a range (other than at potential support and resistance) and you recommend against shifting trading timeframes. Any comments about this?