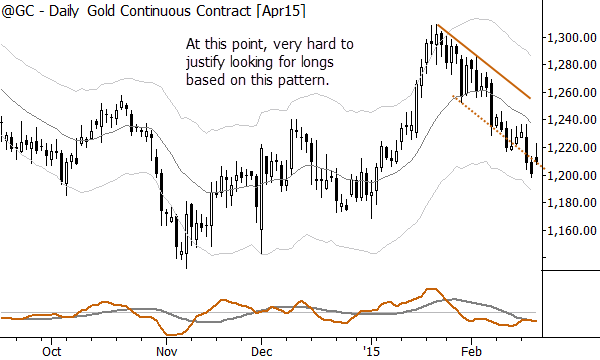

I thought it might be useful to take a look at one of the most common trading patterns, the flag, and, more importantly, to see what happens when it doesn’t work out. If we understand how patterns fail, we are better equipped to trade those patterns, and, sometimes, may find some hidden opportunities along the way.

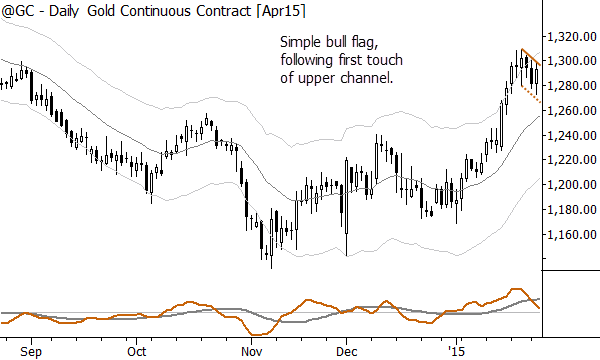

In recent weeks, gold has set up a bull flag. Right away, let’s consider context: I’ve been fairly bearish on gold since 2011, and I was fortunate enough to catch the exact high of both gold and silver for our Waverly Advisors research clients. However, it’s important to remember that a longer-term bias like this is exactly that–it’s longer term. In the short term, there’s plenty of room for play against that bias, and I’ve found myself long gold several times over the past years. So, despite that intact longer term bearish bias, I had no problem setting up a long trade based on the following simple flag:

This is a good example to commit to memory:

- The market had been in a downtrend on this timeframe.

- Sharp upside momentum broke the downtrend pattern. (Keep it simple.)

- The market traded through the upper Keltner Channel,

- and then pulled back, forming a tight consolidation near the high of the previous upthrust.

These conditions set up a trade with a high probability of having at least another leg up. How do you enter a trade like this? There are many ways, but my preference is usually to look for short-term upside momentum to actually trigger the long entry. You’ll see why as this example plays out. A few days later, this happened:

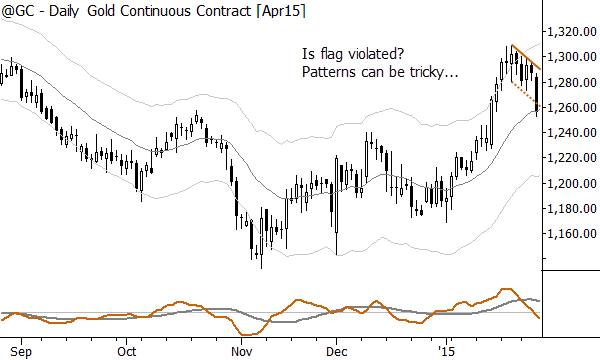

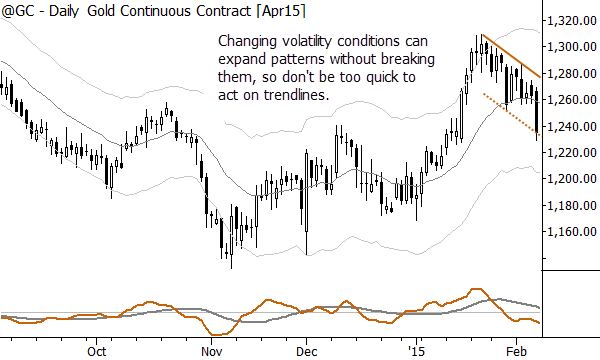

After a day like that, many traders are ready to walk away. In fact, anytime you see a level (whether it’s a pattern broken or a support/resistance level violated) broken, watch what people say–you will see most technicians predict that the market will keep moving through the level, but this is just not the way markets work. Markets are tricky; they like to seduce technicians into making bad decisions. Expect that a market will break a level and then reverse, trapping breakout traders into the trade. In this case, a sharp recovery followed that down day, and we were able to slightly redefine the pattern a few days later. There is an important lesson here: new volatility more often expands consolidations, rather than breaking them. Another way to say the same thing is that most breakouts fail. Here’s our slightly redefined flag, which was challenged a few weeks later with another selloff:

In the caption above, I asked if we were still looking to buy. The answer, at this point, is yes, but remember–we are not long. We have a pattern that shows coiled potential in the market, but that, alone, is usually not enough reason for me to actually have risk on in a particular market. Think in terms of setups and triggers: we need a trigger to act, but that trigger only makes sense in context of a setup. Without both a trigger and a setup, we have no position.

In this case, the setup is the clear daily bull flag. Yes, it’s starting to look “not so good”–it’s taking too long (maybe). There’s too much downside, and too many easy breakdowns, and there just seems to be little buying interest. Overall though, it pays to not give up on a pattern like this because the potential is still there. However, look what happened next:

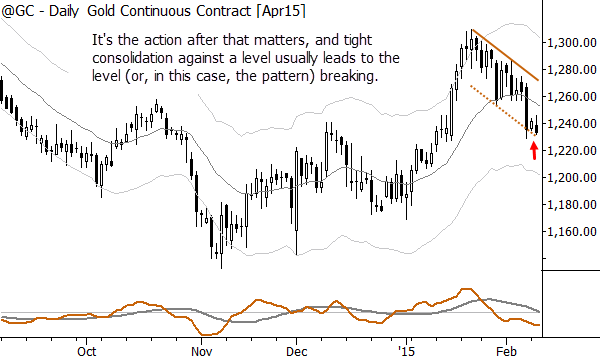

Now the situation is a little different. The first time we had a large selloff, the market snapped back sharply the next day. In this case, we are consolidating near the lows, and this is not good. If we were to drill down into a lower timeframe, we’d find consolidations and patterns that were more or less bear flags near the low of that sharp selloff day. Watch for subtle clues in follow-through–this is more powerful than any sentiment index or volume analysis–everything you need to know is written clearly in price.

This type of pattern is a good warning of impending pattern failure, and here’s how it played out:

Breakdowns lead to further breakdowns, and our reason for looking for a long trade is violated. At this point, we no longer have a setup, so there’s no reason to even consider entering long on a trigger. This is simply a trade that never triggered an entry, and we can wait for something more interesting to happen in this market.

I think there are a few good lessons here: notice how clear the initial setup was. If you have to go looking for a trend change, it’s probably not a great one. We did not give up when the pattern was expanded; don’t assume that trendlines or patterns act like Technical Analysis 101 books suggest they do–the market is not that simple. Though we had a great long setup, we were never long. This is a failed trade on which we lost no money. (It is not fair to say we had no risk, from a theoretical perspective, as it was possible that a trigger could have taken us into the trade. If you are thinking of risk correctly, there was risk associated with this trade, even though we had no execution, but that’s a topic for another day.)

Find your patterns. Know how they fail, and monitor market structure as the trade, or potential trade, develops. Those are the essential tasks of “stalking” a trade entry like this. Markets are not simple, but your goal should be to make your trading as simple as possible.

Hi Adam, Nice post.

1. Were you looking for a bar closing above the upper flag channel before you would have entered long? And if so where would your stop have been?

2. In this instance no bull flag trade was taken as there was no trigger bar. However, if one was trading pullbacks and complex pullbacks there could have possibly been two entries that were taken which subsequently failed. How does one decide whether to a) take the simple pullback, b) wait for a complex pullback or c) wait for the bull flag?

Golden Nuggets in a Gold Chart … Superb !

Good Example of Bearish Failure Test from TAAS course on the Gold Monthly Timeframe.