When You Meet the Buddha on the Road...

“While you are walking on the road, if you happen to meet the Buddha, you must kill him.” So reads one of the more enigmatic teachings in Zen Buddhism (attributed to Linji Yixuan (fl. ca. 850 CE) from a turbulent and most interesting period in Chinese history, if you want to do further reading.)

What does this mean, to kill the Buddha? While many possible interpretations have been offered over the years, the most direct idea is that a student of Buddhism must beware of making a fetish of the Buddha—relying on authority and guides can prevent us from finding our own wisdom. It is a challenge to see the world with new eyes, and to cast off the chains of tradition.

Working within a tradition

Personally, I have great respect for tradition, and have trained/apprenticed in several classical traditions. My music teachers traced their lineage back to Haydn in an unbroken line of teachers and students. This was one reason why I taught for years—to pass that tradition onward. When I studied French cooking, I stepped into a line of cooks who represented the mainline of French tradition—Bocuse, Point, Mere Brazier, Escoffier, Carême, and the list goes on.

Working within a tradition shows you where you fit in history—a mindset that might not be perfectly intuitive in America, where everything is still cutting-edged new. It also means there are some things you do and some you don’t do. There are expectations and standards, and those old names are venerated if not actually worshipped.

There is great value in tradition. Someone has already figured out how to cook onions and make a base for sauces. Someone long ago figured out how to play a scale most efficiently on the piano keyboard. Having to redo all of this work would not be efficient—there is knowledge and wisdom in tradition. People have carved out the essential set of knowledge for a discipline, and this is a good place for a student to begin.

However, there are certainly times where it makes sense to push against the boundaries of tradition—where we have to decide, to paraphrase Mahler, if we are more interested in becoming stooped, old men worshipping ashes, or if we will tend living fire. And this is the practical lesson from the Zen koan: strip away preconceptions and look outside the accepted bounds of tradition. Find your own way.

I’ve always done this with my trading and teaching. My blog is full of posts looking at some of the sacred cows of technical analysis—finding no statistical edge around common tools like moving averages, candlestick patterns, many classical chart patterns (e.g., head and shoulders), and Fibonacci ratios. This has been a big part of my work here over the past decade.

The easy targets

To be sure, some of these “Buddhas” are easy to kill with just a little thought. The “Bible” of classical chart patterns was written by two men (Edwards and Magee) who never traded successfully—yet legions of social media experts splash these pattern names all over charts. One of the famous authors who wrote books popularizing and cataloguing candlestick patterns has admitted that he does not trade and just works as a “consultant” because he can read candlesticks. One of the early fathers of indicators revealed in an interview, late in life, that he was utterly unable to make a dime trading, and that his income from trading books supported his trading losses (a revelation wholeheartedly reinforced by his wife in the interview).

I don't think it's too much of a stretch to say that most of what is taught under the aegis of "technical analysis" is misleading or simply false.

Yet these errors are codified and reinforced by modern “certification” programs, which test knowledge of a set of books rather than seeking truth. This is a highly questionable practice (to be kind). If the books are flawed, people who complete such a certification program might get the right answers on the test, but what happens if those answers are the wrong answers in actual application? What if we are producing people with letters behind their names who have accepted largely false information as “knowledge”?

These are not easy questions to ask, and even asking the question does not gain you much popularity with people committed to the status quo. (But remember that according to the status quo, somewhere around 95% of traders fail!) I’m perfectly comfortable asking those hard questions, and doing so publicly. My Big Five Personality profile includes phrases like “you are less agreeable than 76 out of 100 people,” so being the voice crying in the wilderness, especially in the pursuit of truth, does not bother me a bit.

My challenge

But in this most recent effort to build a new trading methodology, I knew I had to go further. I had to discard everything, or as much as possible. This meant leaving behind the work of classic writers and traders who I do respect, and of modern voices who might have served as guides or mentors. It also meant taking a good, hard look at things I believed to be true in the market. For instance:

- Big moves usually see followthrough in the same direction

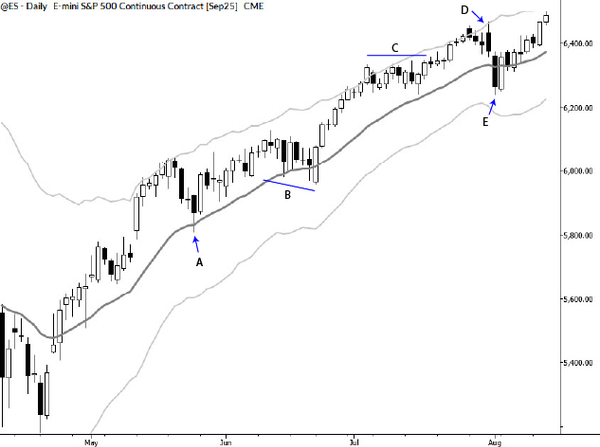

- We can define a trend by pivots and swings—higher highs and higher lows = an uptrend

- Most of price movement is random and unpredictable, most of the time

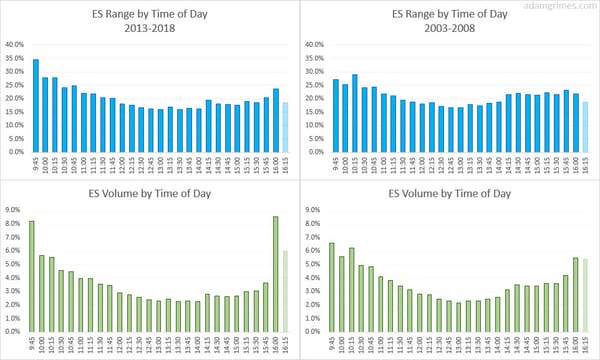

- The trading day usually breaks into three more-or-less distinct segments, with divisions around 11:30-12:00, and 2:30 PM

- Afternoon trends that start before 2:30 usually abort into close, but trends that start later tend to persist

- A reasonable goal in intraday trading should be identifying and capturing trend days (or at least avoiding being on the wrong side of trend days)

- Daily conditions such as volatility compression, multiple closes in the same direction, etc. give an edge to trending action the following day

- Reward in a trade should be at least as big as your risk

Of course, when you start asking hard epistemological questions, things get scary. It’s hard work—exhausting—to literally question everything, and questions about the quality of knowledge (“How sure are we of what we think we know? How do we know what is true?”) are challenging. Sometimes, there are no clear answers.

But the first step is having a mindset that asks these questions fearlessly, and the motivation to carry through the work to find answers. If you have that, the next thing you need is a framework or an approach, and in my next blog post, I’ll share a few of the tools I used to change my thinking on a few important trading topics.