What works?

I post a lot of critical thoughts, and spend a lot of time encouraging people to think deeply about the technical tools they use. Recently, I've received a lot of questions about what I think actually works. Though I've answered this in some depth before (and have written a fairly large book on the subject), maybe a concise post here would be useful.

Conceptually, think of price action as being shaped by two conflicting forces: mean reversion (the tendency for large moves to be reversed) and momentum (the tendency for large moves to lead to further moves in the same direction). Most times in most markets these forces are in balance. When they are in balance, price movement is nearly random. Over any large period of price movement, these force will more or less balance, which is why academic studies still find good support for random walks in market prices. It's also why traders have to wait for their spots, and why you can't simply trade any market at any time.

Are there patterns that can show us if one force or the other is likely to dominate price action over a certain timeframe? That's one way to phrase the essential question that has motivated all of my research and thinking about markets, and it's also one way to think about the problem of technical trading. Can we find patterns that show us when we should be "going with" large moves or when we should be "fading" those moves? In the absence of such patterns (or if they do not exist and market action is random), then we're just trading in randomness and it is impossible to make money.

The good news is yes, it is possible to identify these patterns, and they are not complicated. Yes, there is room for great subtlety and refinement in application, but, at their core, these are simple price patterns. Here are a few examples of price patterns that can tilt the scales in favor of one force or the other (not an exhaustive list):

Mean reversion- Fading large single bars

- Fading N-day runs

- Fading breakouts of N-day highs or lows

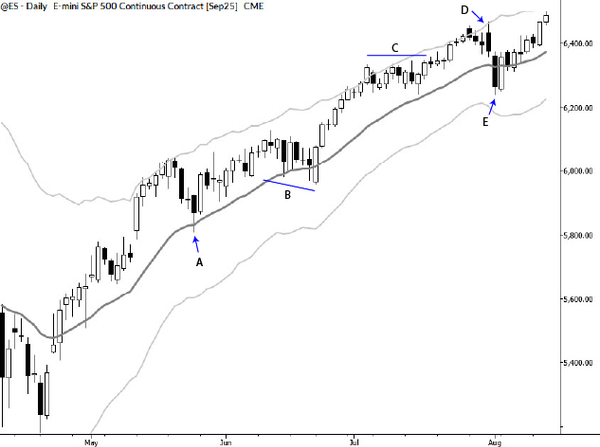

- Fading large excursions from average prices (think Keltner channels or Bollinger Bands)

- Pullbacks

- Nested pulbacks

- Breakouts, in some cases

- Volatility compression

In my experience, this is all there is: the understanding that these two forces shape prices, they are usually in balance, and there is usually nothing to be done in any particular market because there is no edge. The game, then, is redefined as waiting for a pattern that shows there is a potential imbalance, taking a position (the correct position, with the correct risk) to capitalize on the imbalance, and managing the trade as it develops. That is all there is, and it's enough.