Trading the Rally in India: Gaps and Risk

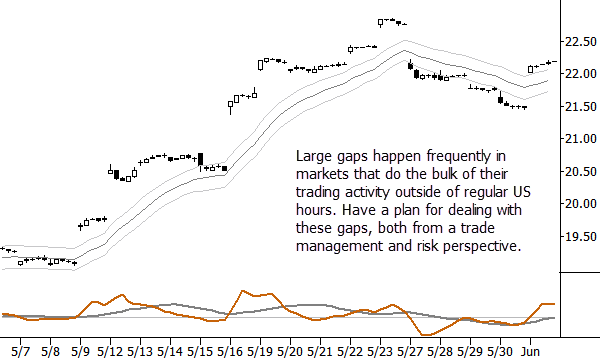

[dc]I[/dc] wanted to follow up on my recent post about trading the rally in India. I ended that post with a question: We were planning to enter EPI (an earnings-weighted India ETF) on a breakout above a long daily consolidation. However, the market gapped open far above our entry price, and the question was what to do?

There are a few points here. First, conceptually, slippage can be a very good thing. Most traders think of slippage as a cost of trading, and, with a simple definition, this is true. Slippage is the difference between the price you thought (hoped?) you were going to get and the price at which you were actually executed. For a very small trader, slippage is minimal, but still very real. If you have a sell stop in an active stop at 12.00, when that stop is triggered you will likely be filled a little lower, maybe around 11.99. As you become a larger trader, your orders will take more liquidity from the book and you will incur larger slippage. This is a major error in many developing traders' thinking: they forget to consider the impact their order will have on the market. Any time you do a backtest, one major deviation from reality is that you were not trading at that point! Your order, small as it might be, would still have had some effect on the market, so things would have been different. A large trader might get fills around 11.94 on that stop, and perhaps much lower in an illiquid stop.

So, traders are conditioned to think that slippage is bad, but I made the point in my book that slippage can actually be a good sign. If you are looking to buy a breakout, you want it to be difficult to buy. Slippage shows that the market has momentum (i.e., other traders are executing the same trade). Slippage shows that there is some urgency behind the move, so, in some trades types of trades, when you are executing around visible inflection points, slippage is a good sign. In fact, "positive slippage" (when the market gives you a gift and you are able to execute at a better than expected price), can be a death knell. This is an example of one of the subtle aspects of price action that can help solidify your edge. Yes, you can probably trade just fine without and awareness of this factor, but understanding how the market should move at the points you identify is an important skill for the discretionary trader to develop.

So, with that in mind, this large gap open could very well a good thing for this trade. What would I do in this particular situation? Pay up immediately and get in the trade. Now, we come to another problem: once we've settled the question of buying or waiting in favor of buying now, there is the question of how much to buy. Let's use round numbers for this example, and assume you were planning to buy something on a breakout of 10.00 with a stop around 9.00, risking 1.00 on the trade. Now, the market gaps and you have to pay 11.00. What are your options? Well, there are three obvious choices, though you could likely come up with other possibilities and variations: 1) you could just execute the same trade with the same stop, 2) use a closer stop, or 3) buy fewer shares (or contracts). Of these choices, the only one that makes sense to me is to buy fewer shares and trade smaller. If you do the trade with the same size and same stop, you've now taken on significantly more risk. If you use a closer stop, that strikes me as just silly. The market has just showed you it is more volatile, so why would using a closer stop make sense?

Note that this solution hinges on a concept that I believe is very important for discretionary traders: each trade should represent a consistent risk to your trading book. In other words, you want to size each trade so that a loss at the initial stop loss is an equal percentage loss of equity. Some traders size trades based on their conviction levels, risking more on trades that they "feel good" about. Such a strategy does appear to make sense on the surface, and it is certainly possible that it does work for some traders, but there are problems. I'm always baffled when people talk about "low risk" trades, and, cynically, I wonder if it's a way for people to kind of "have their cake and eat it too" when talking about trading. You can tell people you are getting into 10 trades, claim they are all very low risk, and forget about the ones that don't work out, while you call attention to the ones that do. (This is an old game in retail-marketing land that is now rampant on the Twitter stream.) The problem is, if a trade is low risk, it also is low reward or low probability. There's no free lunch in the market. You can't risk tiny amounts and make large amounts with a high degree of probability—the market simply does not work like that. As a parting thought, if you are able to identify a set of high conviction trades that you want to take more risk on, ask yourself if you might be better off just doing those trades? Why not just take "A" trades and eliminate "C" trades that do nothing but expend your mental and emotional capital while you pay commissions and other trading costs? At the very least, it's worth thinking about.

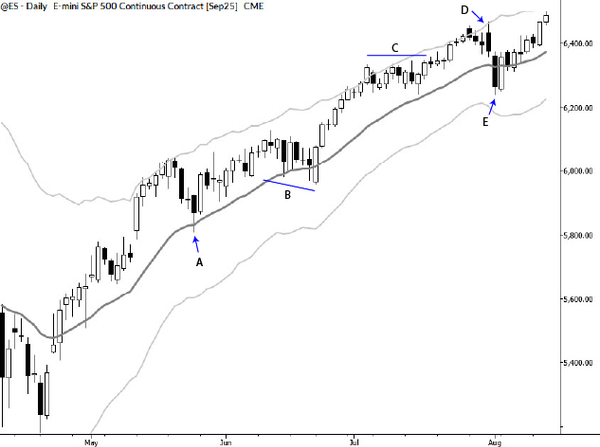

So, just two concepts today, but they are important: Don't be afraid of slippage; be afraid of the easy trade. Be afraid of the market offering you a gift, and, second, consider the importance of sizing your positions so that they represent a consistent risk level to your trading account. Later this week I will write a bit more about how the trade in India developed and how it appears to be setting up for the near future.