Staying in step: finding rhythm of the market

Rhythm is a fundamental aspect of the human experience: our bodies pulse with the rhythm of blood and breath. We experience the rhythms of day and night, and the longer cycles of the seasons. Rhythm is fundamental to music, whether it’s the relentless pounding bass of a rock song, the syncopated stabs of a Jazz guitar, or the nearly baffling asymmetry of Messiaen. Visual rhythm ties together much of architecture, design and visual art. There are natural rhythms in our mood and energy level--rhythm pervades everything we touch or experience, in some way. And, yes, the rhythm of the market is ever present and undeniable.

Philosophically, the understanding of rhythm is a critical division between Easter and Western thought, with most Western understandings favoring a linear perception of time and experience--history, of individuals, nations, and the world, is seen as a journey along a one-way timeline. In the East, a more cyclical perspective prevails, an understanding that events lead to other events in an ongoing cycle of creating and destruction, and that the rhythmic interplay of forces creates much of the human experience. In financial markets, the cyclical approach is usually the right one. This has all happened before, and what has been shall be again, in some form.

The market rhythm

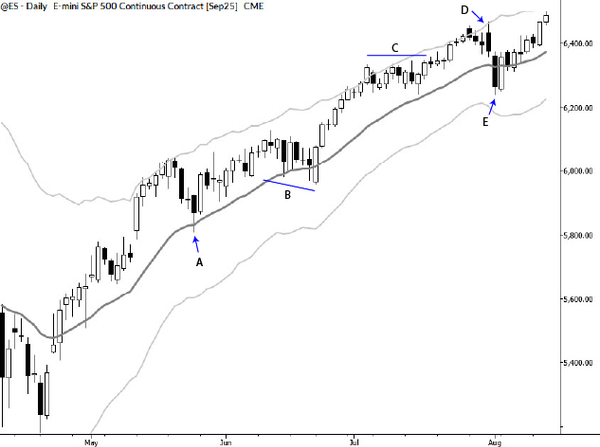

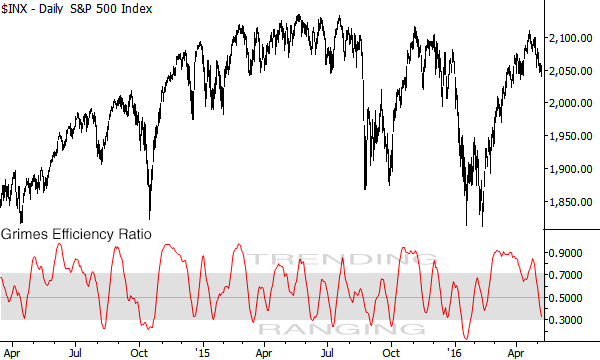

Financial markets do move in cycles and there is a rhythm in that movement. Some of this is well-documented: we can measure cycles in prices and returns with tools like Fast Fourier Transforms or Kalman filters, we can measure cycles in volatility with other tools. The chart shows the S&P 500 with its GER (which is similar to the stochastic and simply averages the close as a percentage of a lookback window. Mid-range values of this indicator suggest a ranging market, while high or low levels shows the market is moving efficiently (relative to its own volatility in one direction—in other words, trending.) A look at this measure shows that markets move between periods of trending and ranging activity with some regularity. There are also many more arcane cycles based on time and angles, and there are certainly cycles in instruments that are bounded and in the relative performance of different markets.

Trading cycles is not as easy as we might expect; cycles shift and abort without warning. To stay in step requires frequent adjustment, and the trader often finds himself out of rhythm with the perceived cycle. Traders who discover cycles often think that they are the answer to many trading problems, but actual application is elusive. An understanding of cycles can be useful, but trading them in a pure form can be very difficult.

The trader's rhythm

Cycles do exist in markets, and this is an area for deep study, but how the market's cycles affect your cycles--the trader's rhythm--there are some lessons here that we can begin to apply right away. First, understand that there is some natural play in all cycles. Do not expect perfect regularity. This applies as much to your trading results and performance as to market action itself—expect that periods of good performance will be followed by lackluster performance. For a swing trader, it is natural to go through periods where nearly every trade wins, and then to hit a rough spot where it seems you cannot do anything right. Just know that this is part of the "game": you're never as good as it seems during the good periods and never as bad as you feel when things are hard. Your overall performance (and the right way to think about your performance) lies somewhere in the middle.

Also, realize that your activity in the market will be governed by the market's action and the variation in that action. There will be times when active trading is required, and times when the right thing to do is to do nothing. Sometimes, you may go through long periods of time in which your only job is moving stops and managing open positions, and you may see these open positions stopped out one by one. This is all ok, and all normal. Your job is to do the right thing, not to find good trades, so just know that this is a completely normal part of the trading experience.

Staying in step

In my experience, a lot of the bad things that happen to traders happen when we try to apply the wrong tools for current market conditions--the tools may well be great tools, but it's just a case of doing what might be the right thing at the right time. (Examples: applying a mean reversion system to fade a strong trend, a daytrader forcing trades when markets are dead, etc.) So the first line of defense is intellectual: know that markets are cyclical and know that your performance will also have some cycles and rhythm.

The next piece of the puzzle comes from good record keeping and analysis of your trading results. Your intuition about your performance may well be valid, but it's a lot better if it's supported by some data. Simply keeping a running total of, say, your last 20 trades' win ratio (assign a 1 if the trade is a win and a 0 if it's a loss (decide what to do with breakeven trades too), and keep a moving average of the last X trades) can give some good insights into performance. Of course, monitoring P&L will get you into roughly the same place, but win ratio is often a good early warning sign.

Last, have good rules that help you decide what to do. The right answer, of course, is the standard and not-immediately-helpful "it depends", but it does depend: it depends on what markets, timeframes, and style of trading you do. At one extreme, a long term trend follower may well ignore this information, knowing that she is simply going to be out of step with the market for most of the time, and also know that it doesn't matter because she will be profitable over a long enough period. On the other extreme, a daytrader might pull the plug on a day if he has 5 or 6 losses in a row, because he knows that is unusual for his style of trading and probably reflects a market where conditions are not favoring his play. It's hard to know what these rules should be until you've traded a while, but developing these "meta rules" that govern your behavior and trading activity is an important task for the developing and professional trader alike.