MarketLife Ep 41 - Randomness: why it matters and how to understand it

I received a good question from a listener, Alex:

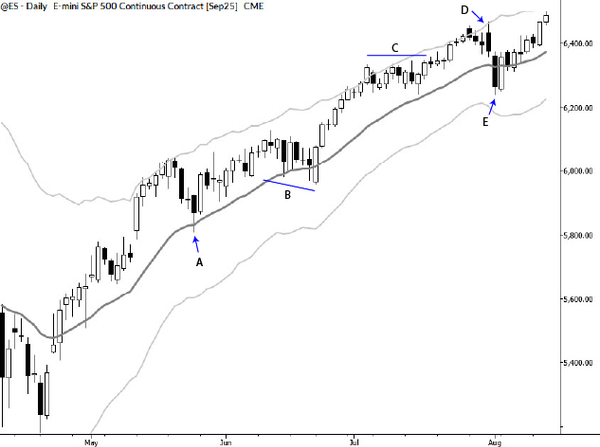

I was talking to a friend of mine (who is a physicist). " I presented him with some market statistics that seem to hold true in many markets, e.g. that the market has only a low probability to hit yesterday’s high and low on any given day (10-15%, depending on the market). My friend argued that in order for a statistic to be significant, I’d have to test it on randomly generated market data. Only if the random data does not show the same tendency, a statistic can be thought of as showing a bias. Do you think that my friend is right? Are statistics only significant if randomly generated data does not show the same tendency? What if both, real historical data and random data show the same tendency? I’d love to hear your thoughts on this. Best, Alex"

This podcast ended up being a bit more involved than most, but I hope you find it useful and entertaining!

Here is a link to the academic paper I mentioned in the podcast.

If you enjoy the podcast, one of the very best things you can do for me is to leave me a review on iTunes here. Also, if you like the music for this podcast, then be sure to check out Brian Ashley Jones, my friend, and a fantastic singer-songwriter.

Enjoy the show: