Doing the right thing: Bias, opinion, and action points

One of the great things about writing a daily research piece is that it serves as a good record of my thought process and perspective on markets on each and every trading day. (Hint: developing traders might try the same thing. When I was figuring all this out, I wrote a daily "newsletter" years ago even though I had no clients. The discipline of doing the work every day, staying in the workflow, and expressing my ideas in a concrete format were an important part of my development process.) In the piece I write for my firm, Waverly Advisors, we publish a broad perspective on a wide range of markets, but also "actualize" those perspectives into executable "trade ideas." Today, I want to spend a few moments thinking about the difference between bias, opinion, and executing concrete trade ideas.

Three layers deep and more ways to lose

To put this into context, I tend to think of each market activity as having at least three components: my opinion about what might happen in the market, my longer term perspective, and shorter-term "action points." Let's start with the first one of those: having an opinion can be hazardous to your financial health. Right away, here's where I think a professional, technically-driven approach separates itself from the pack; so much of what is written or said about financial markets is opinion and speculation. Even experienced, wise people will talk a lot about what might or might not happen, and possible fallout. Many smart people get into markets thinking they are going to "figure it out." If you have an engineering background, then you think you're going to apply one set of tools. If you have an MBA, then you think another set of tools will work. The problem is that none of this really works very well.

Markets are beautifully, wonderfully, and maddeningly counter-intuitive. If you think you're going to figure out the news and be positioned correctly, good luck. In actuality, it just becomes more ways to lose. For instance, let's say you have a thesis that you want to buy oil stocks because you think the US Dollar is going to be weak and so crude oil prices will rise. How could this go wrong? :) Well, perhaps you're wrong on your USD forecast so you do not pass go. However, you could be right on the USD, but then oil doesn't move how you think it will. Or maybe the USD forecast is right, crude oil moves as anticipated, but the stocks don't move in response to oil because something is holding down the stock market. This is an admittedly simple example, but a lot of "macro thesis" ideas actually fall into the "more ways to lose" camp. In this example, the actionable part is that you think the USD will be weak. Trade that. Get short the Dollar instead of making all these connections to other markets. Trading is not an intellectual exercise and it's not a chance to show how smart you are by creating business school case studies.

In my experience, you can't help but have some opinion and bias on what you think might happen. You'll have to find the right answer for yourself, but, in my experience, the right thing to do is to ignore that bias. It's often emotional, perhaps driven by political considerations, and swayed by the zeitgeist, social and mainstream media, and by my own unstoppable contrarian slant. I know, or rather have learned, that this bias is a very unreliable guide and so I ignore it.

Longer-term bias

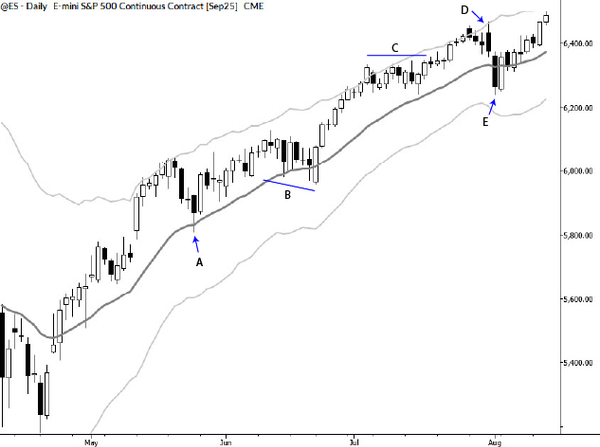

The other two parts, my long term bias and action points, are more important. The challenge comes when action points align against your long-term bias. There are many traders who will tell you not to trade against your bias or the longer-term trend, but I'd suggest that might be wrong. Your longer-term bias will sometimes simply be wrong. Your action points may align against your bias (which, let's say, is driven by the longer-term trend), and those action points may show where the longer-term trend is breaking down. Consider this: you have a market that is a strong downtrend on the weekly/monthly timeframe and then you start getting daily buy signals. Do you ignore those? Many technicians say you should, but these can often be outstanding trades since those long trades might show where the trend is ending. (Gold, in recent months, is a great example of this.)

To assume we never trade against the longer-term bias is to give too much importance to longer-term trends. Trend indicators are unreliable. In this post, I show that one of the most common ways people use moving averages (filtering based on higher timeframe trends) actually puts you, very reliably, on the wrong side of the market. Too many people complicate things too much with multiple timeframe analysis. If you are going to have a bias, you've got to figure out how to manage it and how to keep it from hurting you. This post is a couple of years old, but applies just as well today. If you don't want to read the post, I'll make it simple: any bias you hold should be based on something you can see in the market. (This removes "opinion" from consideration.) It also should be falsifiable, meaning that you should be able to explain what would invalidate your bias. If those two things are not true--it's not based on something you can see and you can't say what would make the bias wrong--then you don't have a bias; you have an opinion. The great thing about this business is you get to choose--you can lose your opinion or you can lose your money.

Action points

Action points are easy--when you get a signal to do something you do it. This is the discipline of trading, and it's also how you build consistency. This point really could have been a lot shorter and could have simply been: when you get a signal from your system, do what it says to do. Period. All of these other things might be part of your system, but they need to be incorporated in a way that makes sense.

I'll follow up with a post soon that shows the real difference between bias and action, and between being right and making money. The Brexit event provides a great backdrop; our Waverly Advisors trade recommendations had us positioned short USD and long stocks into the event. We were wrong--quite wrong--yet our recommendations were profitable. Understanding how and why will drive some of these lessons home, and give you some ideas for building your own system, methodology, and approach to making money in the markets.